|

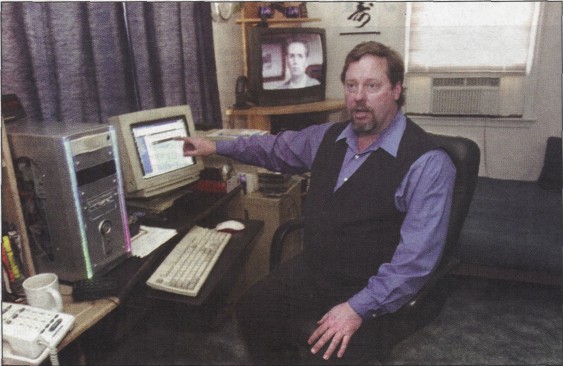

As the beat of war drums

continues, so does the

cadence inside a Mt. Jackson

residence as its occupants step up efforts to warn of invisible,

blistering and suffocating enemies Americans troops

may face on the ground in Iraq.

The two U.S. Army veterans were in

the Persian Gulf back in 1991 during the first war in the region,

where both say they were exposed to chemical and biological agents

that left them disabled.

Twelve years later, the military is

no better equipped to deal with these threats than it was the

first time, both say, and people are going to die.

|